Why I'm mad about wild camping, click-bait and infuriating entitlement

The outdoors is not a commodity to be exploited

Wild camping, land access and the age of social media make a tricky boiling-pot of issues from start to finish. Last year, I muted, unfollowed and even blocked a few of people on socials because of how they posted about hiking and wild camping, especially here in Cornwall. Some of these folks were even people I know in real life, but I was fuming every time I saw their photos.

I feel a bit funny about being so cross about it, and I didn’t know what else to do except try to not see the images. These people were making me feel sad, mad and frustrated about how we use our beautiful, great outdoors. And, because discussions can be so polarised these days, I didn’t see a way to start a conversation about it without causing offence, without people assuming I was only thinking ‘one way’, or by being called a hypocrite.

Let me be clear:

I absolutely believe that we should have much more freedom to roam, explore and access wild spaces than we do, and that it’s unconscionable that so much land sits exclusively in the hands of a few hugely wealthy folks as part of private estates.

I believe and know firsthand how healing, exciting, uplifting and wonderful it is to hike and camp wild in the great outdoors. I’ve been lucky enough to do it for long periods of time (but rarely if ever breaking rules to do so).

I think everyone should be able to camp outdoors, that there should be oodles more common land, and that we should be able to experience being and feeling free in nature: it’s our habitat and we are deeply estranged from it to our detriment (and the detriment of the NHS, workplaces and beyond).

But these things are not possible in the way we might want at the moment, and for more reasons than just a few rich people barring us from walking on their land because they’re selfish pricks. Yes, there are unfair ‘rules’ but that doesn’t mean we should just break them, shouting ‘F*ck the man!’, or ‘F*ck the Tories!’ for their erosion of protections for nature (but absolutely f*ck them), or ‘F*ck Darwall’ for trying to take away our right to camp on the last legal camp spot on Dartmoor (but also fuck him too). Protest is vital and important, but individuals being selfish about what they want from nature (aka more likes and clicks on socials, and a pretty space to sleep by the sea in a tent) under the guise of ‘protest’ doesn’t help anyone beyond themselves, and they then become part of the problem too.

There are enough problems, and there are better ways to solve them. The whole thing needs a deeper dig to understand the bigger picture and I’m not trying to solve anything by writing this one post, but I really needed to get it off my chest and explore some of the issues.

The need for restored connection on every front

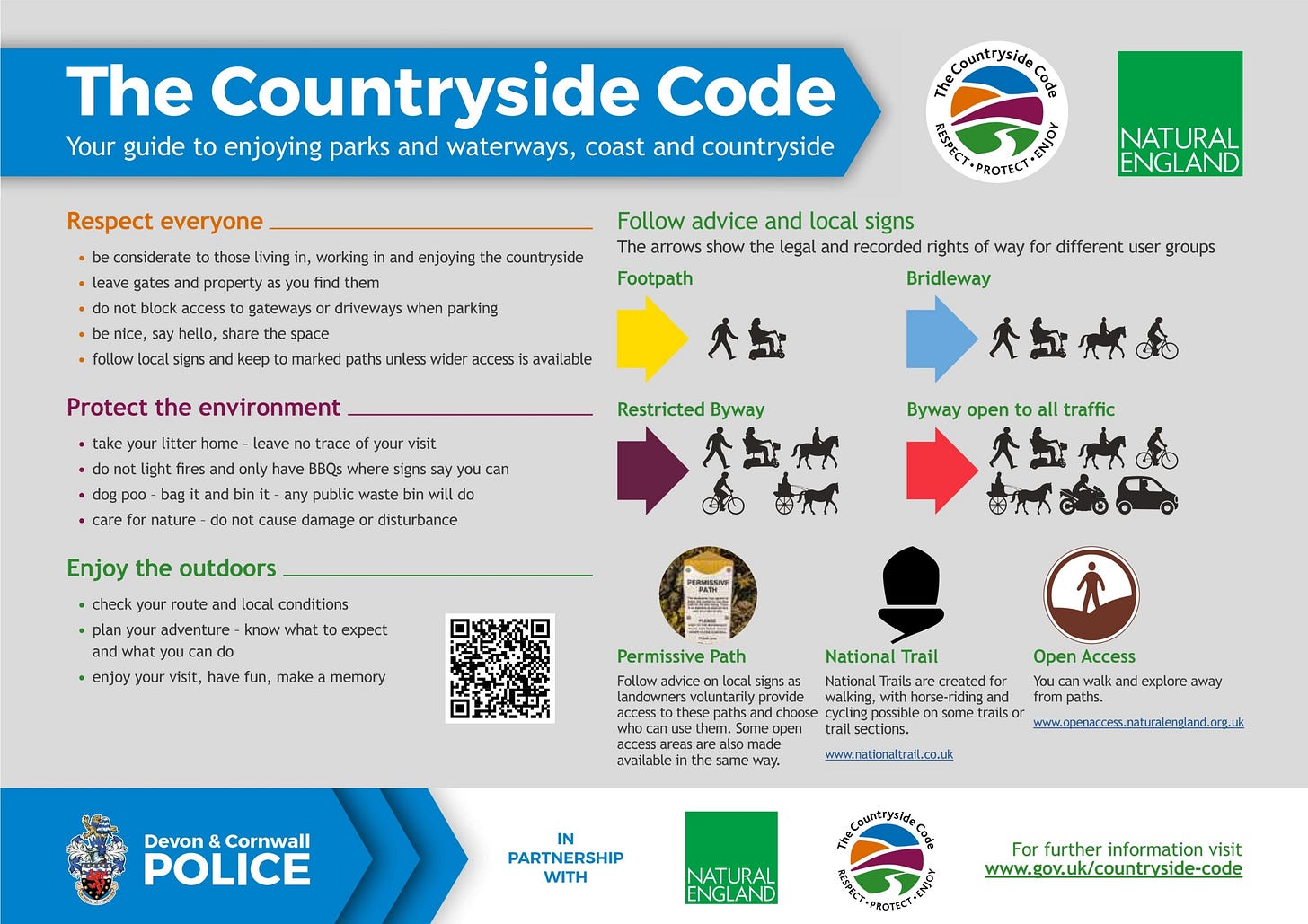

There’s such a lack of foundational connectivity these days; connections which used to exist, and that informed how we would use and access wild spaces. We would understand where our food came from in more detail, we would be taught the countryside code in schools, parents would know how to take their children outdoors and guide them in how to respect it. And besides all of this there were just…. less people. Less people generally, and less people needing, wanting or being aware of the outdoors as a beneficial and recreational space.

It’s great that more people want to access nature, but there has to be ways to support that happening without the outcome being that people destroy the very things they’re seeking to enjoy. We need to begin to tackle the issues at their root, and that’s got to be with education; inside and outside classrooms, and for all ages of folks in all places. We’ve got to plug people back into their innate love and respect for the natural world and awaken the inherent connection to it that exists within every single one of us. Somehow we must backfill all the gaps that have been created by decades of knowledge erosion from curriculums, communities and our culture, so that we can stop treating nature and the outdoors like commodities that are “OuR RiGhT tO uSe!!” Instead, we need to see the outdoors as an extension of ourselves and something that needs to nurtured and approached with respect, rather than being used as a means to our own ends and desires.

“But IT’S MY RIGHT!!!”

Yes, I totally get that it’s infuriating to be told you can’t camp when you’re walking long distances outdoors and want to feel like you’re back to nature, or can’t afford a campsite, but that doesn’t give you the right to think ‘f*ck it’ and do it anyway, because more is at stake than your one night under the stars. There are many complex reasons why it’s not just as simple as saying ‘it’s my right’ and encouraging others to do the same. In fact, in doing this, it makes the muddy waters and difficult relationships with farmers, landowners, stewards and others, much, much more challenging to resolve.

I also walked the whole 630 mile South West Coast Path in 2020. I’m Cornish, born and raised in Falmouth where I still live, and I feel passionately connected to the land and the sea here. If anyone ‘had a right’ to camp wild on the coast then it might be someone like me, but I f*cking didn’t, because it’s not allowed, and because people were following me on social media who also aspired to hike distances, just as I had followed and learned from people too. My not-wild camping doesn’t make me a goody-two-shoes by the way, or a scaredy cat of breaking the law. I didn’t camp illegally because everyone who looked after the land I walked on was pleading with the public to NOT do it and especially not to publicise it, so why the f*ck would I decide I know better? I posted on my social media nearly every day of that hike; sharing beautiful images, historical details, amusing running commentaries about the highs and lows of the adventure, but not ONCE did I post about camping wild, or sneaking my tent behind a hedge or having a fire on the beach, because that’s not an example I want to set, and it’s not the legacy I want to leave Mother Nature after I’ve enjoyed my experience with her. I am not just going to take.

I would receive messages every day of my hike from people asking if I was scared camping wild, or how I planned my places, or how I sneaked my tent up without being spotted. Every time I’d reply kindly and warmly, explaining that if I looked like I was ‘wild camping’ that it was because I’d found the name of the farmer or landowner and called them ahead to ask if I could pitch a tent in their field and be gone first thing, so that they had a chance to say yes or no, and or tell me yes but also let me know about pregnant livestock or a dodgy bullock close by. I wasn’t so arrogant to think I had a right to potentially disrupt an ecosystem that wasn’t mine, just because I want to pitch my tent somewhere pretty and post about it, hoping it boosts my ‘image’. Nope. No way.

When you tell people something’s ok or even imply it (when it’s not) and then don’t give them any way to learn about how to do it responsibly, bad things often happen. Just ask the rangers, volunteers and stewards of our national parks, beaches and wild spaces through lockdown about how much trash, human sh*t, discarded gear and debris they removed after irresponsible wild campers descended because ‘it was their right’. The destruction to nature they caused, and the damage to relationships with those communities, still last to this day.

Here are some infuriating photos from articles in the BBC, ITV and the Guardian around the time of lockdown easing. Things are not much better now.

I won’t lie – I wanted to wild camp when I hiked the coast path because it’s wonderful, and I was annoyed that I wouldn’t let myself do it. My SWCP hike was undoubtably harder work for me because of it. It involved extra planning, walking further off trail to get to a campsite that had space, sometimes getting a cab to a site further away or making calls to local landowners and engaging in chats that didn’t always end in a yes. It wasn’t as simple as walking and stopping to pitch wherever I wanted, but the inconvenience was outweighed by knowing that I wasn’t causing damage as I had fun hiking. I ALSO knew that I wasn’t encouraging others to do damage either, or leaving people aspiring to something without any information of how to responsibly engage with it.

It’s not sustainable to put beautiful, fragile places on Instagram on blast with pictures taken to boost your own exposure and popularity; often the very reason these places are so beautiful is because they’re hard to find, need word of mouth and are not frequently visited. When people expose them, especially for the purpose of encouraging ‘fun-times’ with illegal camping or recreation, all they’re doing is exploiting their vulnerability and contributing to their destruction, and then just walking away to the next place to do the same again - enjoy themselves and grow their platform.

Perhaps it’s because I’m Cornish and was raised with deep reverence for the natural world, or perhaps because I’ve seen Cornwall used, exploited and her cultural heritage eroded over years of second-home ownership emptying out our villages and excluding our local communities, but I have long been averse to posting on my social media in this way. Yes, I’m pretty sure that if I dig back I’ll find plenty of pictures of beautiful places, but I deliberately never post exactly where they are or how to get to them unless they can sustain or are used to potentially larger traffic. I’m always vague, usually whilst simultaneous giving some useful info and context. I’ve gotten lots of grief for this, with people in comments telling me I should say clearly where it is or I’m just being a click-bait tease, attention seeker or gate keeper. Err no! F*ck all the way OFF with that attitude. Get a f*cking map out, or go on Google, and do some research yourself to find lovely, out-of-the-way places. If people are trying to order up pretty places on social media to visit, without all the effort and work of discovery, then just get a VR headset and go there that way (you lazy, rude wally). The great outdoors is not a convenience food.

My next adventure is no different…

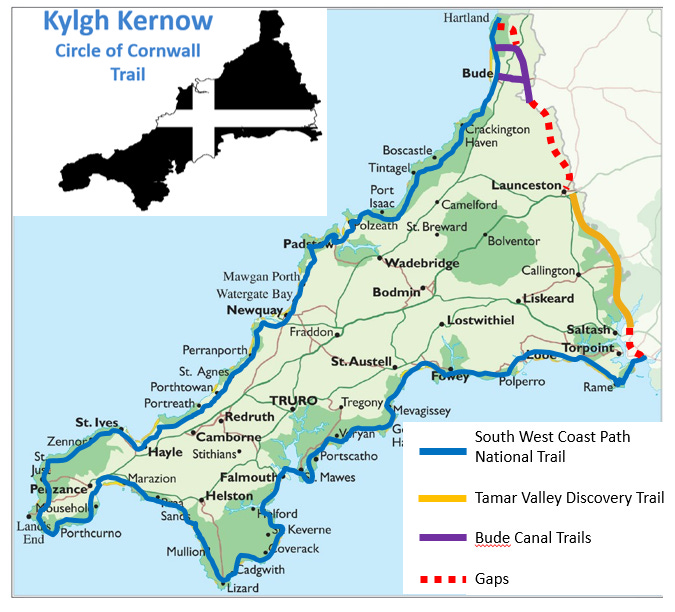

I’m experiencing similar frustrations with the issue of wild camping as I plan my Kylgh Kernow (circle of Cornwall) trail for April and May. I’ll following the SWCP, and then crossing along the border with Devon inland on the new Tamara coast-to-coast to make a roughly 380 mile loop around the edges of my home county.

It sounds wonderful, and it is, but because I want to post and write about it publicly then I have a responsibility for what I share, and wild camping isn’t a part of that. So I’m spending a long time finding ways to get to campsites, to use my van (responsibly), and to make sure that I’m not part of causing problems whilst doing something I love, in place that I love. It IS possible, and feels so much better to know you’re a leaving a lighter touch and causing no harm. (More fun stuff on this trip soon by the way!)

Am I a gatekeeper?

It would be easy to accuse me of gatekeeping; of keeping people away from something and attempting to limit access yet experiencing that thing for myself, but I don’t believe I am. The more these polarising words like ‘gatekeeping’ get bandied about, the less we can really chat and resolve the genuinely important issues. In fact, where does the line between gatekeeping end, and the mission to preserve unique, important cultural and natural heritage begin? (It’s a debate for a different piece, but Cornwall is an excellent example of this conundrum.)

If it helps clarify, then let me be a bit more explicit about the kind of things I personally saw (and see) on socials that were pissing me off so much that it caused me to unfollow and block people I know, as helps to illustrate. Below are just a few examples of the kind of images and content, from people who purport to love Cornwall, be Cornish, and support the great outdoors:

Photos of a tent pitched on (fragile) sand dunes on the North Coast (not permitted), with descriptions of how beautiful it was and no one else was around and it’s easy to hike in and pitch and cook on the dunes and watch the sun go down. (with #leavenotrace slipped in at the end as one of the hashtags for some social responsibility/greenwash that conscience)

Images of #vanlife vans camping illegally on passing places for ambulances etc. on narrow roads (e.g. Durgan) to be in ‘a perfect spot for a wild dip first thing in the morning’.

Reveals of ‘secret spots’ that only locals know for swimming in places like Cadgwith, along the Helford or others, with all details you need to get there, info on how to ‘scramble down’ the fragile ecosystems for access, and places you can leave (dump) a car on the road close by for ease etc. etc.

Images of tents pitched on scenic spots on the SW Coast Path (not permitted) extolling the glories of hiking and pitching wherever you want along the path, (a la Raynor Winn) when the National Trust, local farmers and local residents are desperately asking people not to do so for a range of excellent and understandable reasons around livestock, livelihoods and preserving natural ecosystems.

‘Wild Cooking’ on rocks and pebbles on Grebe Beach (one of the most precious places I know locally and special to so many of us) with ‘easy to follow recipes’ showing a whole cooking kit. Lots of encouragement of how easy it is to do, accompanied by photos of pitching a tent and camping down there because no one checks (#leavenotrace of course).

Oh my hat, it makes me SO f*cking cross! At the risk of being a broken record, it deliberately encourages others to do the same, without sharing rules or how to set up and leave with no trace, which then causes locals/ landowners/the NT etc. to be increasingly frustrated and unlikely to want to discuss access in future. It’s short sighted, because it risks tamping any spark of conversation for wider access and education for all.

How about seeing it this way

As another way of seeing it, I’d like to draw your attention to the philosopher Kant and his categorical imperatives; one of which was his universalisability principle. Although this absolutely has flaws and isn’t always easily applicable, it says in essence that if you do an action, then everyone else should be able to do it. Ergo you should only do things you think would be ok if they were done by all. For example, you might chuck litter out of your car window thinking that it’s only one thing and it’s only you, right? But if EVERYONE did it, then the results would be catastrophic. This same principle can be applied to wild camping, cooking on the rocks on the beach or parking your van in a beautiful ‘no overnight camping’ spot by the sea. If you do it, you think it’s fine because it’s just you and although it might be illegal, disruptive and annoying for those who live near, own or work on the land, you think you’re doing no harm. But what if everyone did it? What if everyone broke the law and rules to wild camp where they shouldn’t, and came to the same spot? It wouldn’t be a beautiful utopian commune where we all gather in nature peacefully, no matter what you’d like to think. It would much more likely be a (literal) shit-show of human waste, voices, noise, trampling flora, disturbing fauna, and causing all manner of fragile relationships in communities both human and natural to fragment. In this light you can see how utterly selfish it is to consider that ‘it’s just you’, but then to post about it all over your social media making it look super appealing and aspirational when you know it’s not permitted, and even more than that; when you know you’re not providing the education and socially responsible information in your posts to be sure those that follow your example aren’t going to come and cause more damage.

(And by the way, the reason no one else is there and it’s so peaceful is because everyone else is denying themselves that experience because they’re prioritising protecting the land and the spaces before themselves. That’s why. And that’s why you’ll cop a load of stink-eye stares from people in the morning - you deserve to.)

If you cook on bare rocks on Grebe Beach you leave hot rocks behind which can cause all kinds of problems. You also scorch them when you have ‘fires’ on the beach, and they stay scorched, just like sand stays black and scorched if you have a fire on a beach. You can walk away from it but it’s not ‘leaving no trace’, because it doesn’t look the same as when you arrived. It’s not ok to bury your hot fire embers, because dogs dig them up in the morning and get burned, or kids do. It’s not ok to leave scorched pebbles and rocks on the beach after your nice cooking session, because those then change their appearance and affect the beach for all other creatures who use it.

It's not ok to pull down branches and sticks off trees to make fires on the beach, on trails or on the moors for your ‘aesthetic’ and because it feels like you’re ‘wild’ – that’s green wood that won’t burn properly and you’re damaging nature. You also should absolutely not pull up moss to lay over scorched ground where your bbq burned the grass – that moss was perfectly happy where it was growing, and now it’s going to die covering up a spot you already destroyed for a 3 hour (smoky) blaze.

It’s absolutely not ok to do all of these things for your social media clicks and likes and shares.

So what do we do?

Answers and solutions to these issues are not easy, and I don’t pretend to know how to fix them simply or fast, but I think those of us that use the outdoors and have the privilege of some education in the arena should be sharing that knowledge in helpful, honest and supportive ways.

Some brilliant suggestions came in on Instagram when I shared that I was writing this post. There were ideas around permits for wild camping, a course and qualification to be able to wild camp legally (like a driving test idea), or ‘leave no trace’ meaning leave no trace on social media either! Lots of creative options, whether you like them or not, and sharing and discussing things like this might be where we’ll find breakthroughs together.

Until government catches up and priorities the great outdoors in its policies and curriculum plans, we have to help protect it and help those who want to enjoy it. And if we have the benefit of a few people paying attention to us on our platforms, then that’s a perfect place to start. I’m not saying we need to be patronising and nannying d*cks, hectoring through our posts, but the very least we can do is model good outdoor etiquette and hope anyone watching us follows suit. Yeah, we might sometimes break the rules too, or get it wrong, but if we’re trying our best then that’s pretty dang good. And, if you’re going to break the ‘rules’, do it the right way: quietly, respectfully and really, truly leaving NO trace.

Thanks for reading, and I’d super appreciate you contributing your thoughts below. I know I might get hammered for writing this but that’s ok if so; I’m not claiming to be perfect and don’t get it right all the time by any means! I’m also sure you all treat the outdoors brilliantly by the way, and I’m not trying to patronise you or think you don’t already know the above. I just wanted to both vent (😬🤣) and open up the topic here. I look forward to your thoughts. Please also share this piece if you think anyone you know might like to read it (even if they want to come over and give me some sh*t about it). Ha!

Much love as ever,

Gail x

Living in the Lake District I can fully relate to this. It breaks my heart to see what some people will do to places of beauty in pursuit of their own enjoyment.

I think you have done a great thing writing this. We live by the principle “Do least harm” (sadly there is rarely a case of no harm..in a trek you can tread on something (eg a worm)) etc. Be responsible for the footprint you leave in the world, own it and being able to justify your choices it the most comforting for us, and I hope the community and nature. No we aren’t hippies, we are just conscious of our actions in a Utilitarianism manner. Go Gail. speak up and encourage other to think.